I’ll admit I’ve never been a big fan of the North American ghazal. There was a point a few years ago when it seemed that everyone was writing them, but I didn’t find most of these manifestations particularly interesting. Or perhaps I should say that, for me, North Americans’ adaptations of the form didn’t push the boundaries of what they were doing to justify all the hullaballoo. For some poets, it seemed to me the use of the ancient form was merely a vehicle to claim access to an artistic tradition (with some post-colonial implications) that hadn’t been deeply considered or adequately understood.

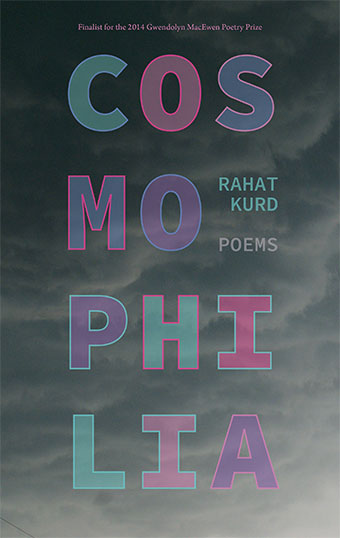

My friend Rob Winger disagrees with me, and he wrote a book of his own ghazals AND a fine essay for Arc Magazine on the subject that you can find here. So, allow me to back away from big generalizations and get to the point of the matter, which is that my (perhaps misguided) reservations were temporarily tossed aside when I read Rahat Kurd’s “Ghazal: In the Persian,” from her book Cosmophilia (Talonbooks 2015).

Rahat Kurd herself is a Hamiltonian by birth with Kashmiri Muslim ancestry, and it’s fair to say that her relationship to her heritages – her Canadian heritage, her Muslim heritage, her Kashmiri heritage, her Urdu heritage – is a complicated one. There isn’t space here to go into the all of the issues that run through Cosmophilia but they present a full range of responses to the position she inhabits in her linguistic, religious, political, and social world. Suffice it to say that the book does remarkable things by sitting “comfortably in its discomfort” when it comes to the traditions Kurd is playing with. She’s not afraid to critique those traditions, but also continues to derive nourishment from them.

Skip this next paragraph if you already know about ghazals.

If you don’t, it’s worth pointing out that they were developed as far back as the 9th century Arabia, but were closely associated with Persian poetry of the 12th century, and with Urdu poetry in the 19th century onwards. In its traditional form the ghazal has a few very specific tropes (I’m mostly copping this list from Rob Winger and a few other sources, so consider my ignorance only scantily clothed in others’ knowledge):

- A series of couplets that don’t inherently cohere in logic or argument or narrative. This is one of its most compelling features.

- There should be at least 5 couplets, and each traditionally uses the same rigid meter, chosen by the poet.

- Each begins (at the end of the first two lines) with a refrain (or radif) that is subsequently repeated at the end of each couplet. In the poem here it’s “in the Persian.”

- Because of this refrain, you end up with a rhyme scheme like this: aa, ba, ca, da, ea, etc.

- The final couplet includes a pun or reference to the poet’s name or pen name.

Kurd has mastery over all of these tropes (except the use of regular meter), but applies them delightfully to an extended argument with herself about how uncomfortable she is in the tradition she is emulating.

So, to the poem:

Ghazal: In the Persian

What secrets – and from me! – you kept in the Persian!

Rules beg to be broken as I grow adept in the Persian.

That love Faiz refused to give again, Lal Ded refused from the first.

Her fierce solitude sparks panic in every soul, except in the Persian.

Must it always be war when we meet? The times we meet are so graceful—

Your elegant farewells never falter, never ask me to return in the Persian.

I lost Urdu as I lost Kashmir, every time I left my beloved women.

I found a circuitous way back to them, uphill, by stealth, in the Persian.

They ask me, after such bitter loss, what possible consolation?

I tell them dry-eyed in the English: I know how Khusro wept in the Persian.

The spy blunders most where he hoped to impress.

Licensed to kill it in Arabic! The joke’s inept in the Persian.

The warmongers jeer: “Even the Taliban write poetry!”

But my improvised device pulls Sunni closer to Shia in the Persian.

Listen: Shujaat Husain Khan weaves Mevlana in the sitar strings of Hind;

Kayhan Kalhor bows his kamancheh’s deep approval, in the Persian.

As a serene heart? Rahat’s that comfortable in the Persian.

As paradox? Being Rahat’s kheili mushkel in the Persian.

— From Cosmophilia, Talonbooks 2015, reprinted with permission

First, to speak of ignorance: one of the things the poem does is quickly introduce us to a host of names, so that ignorant readers like myself can begin to familiarize themselves with a rich tradition. It is clear the speaker of the poem sees herself within that tradition, finding “a circuitous way back,” even if she doesn’t feel 100% welcomed by it. The second couplet refers to Faiz and Lal Ded, and by the time we finish I count five poets and musicians (plus Mevlana, a pseudonym of Rumi) who have been added to my to-read list.

But Kurd doesn’t leave herself off the hook, either, beginning her poem by admitting that the object of her affection has kept secrets from her in the Persian. She is slowly “grow[ing] adept in the Persian,” but clearly doesn’t feel that she can make grand claims in it yet. Because of Persian influence on the form of the ghazal, and thus on Urdu poetry in general, a poet working via Urdu poetic forms must work her way “through the Persian,” in a sense. In the same way that a poet writing in English will undoubtedly have to work through the King James translation of the Hebrew Bible, a contemporary poet in Urdu with any sense of herself must confront an inheritance that originates in Persia.

Who is the “you” in that opening line? “What secrets – and from me! – you kept in the Persian!” On the one hand, following one of the traditional tropes of the ghazal, it seems to refer to a specific lover (perhaps lost, perhaps fluent in Persian?), who has kept secrets from our speaker. On the other hand, ghazals frequently blur the line between a romantic addressee and a more mystical one (cf these poems by Rumi, or John Donne’s “Batter My Heart…”). The “you” here could also be the literary tradition itself, keeping secrets from our aspiring poet who wishes to imitate a form whose greatest works she cannot fully access because she can’t read them in the original.

The opening couplet also lets us know that all of these issues can be addressed with a bit of humour. The odd way she offsets herself “and from me!” in the opening line is almost cartoonishly aggrieved (I’m hearing Miss Piggy’s voice, “You kept secrets? From moi?!”), and establishes an ironic tone that serves Kurd well throughout the poem. This wit will also appear in the last couplet when she uses the phrase kheili mushkel. (I admit I had to ask her to translate this.) “Mushkel” means “difficult” in both Urdu and Persian, and “kheili” means “very,” but only in Persian. So it’s as if the poet has reached a point where, despite her continuing awkwardness with Persian, she recognizes there are things she can say only if she uses it.

Hm, now I have a problem. I’ve written almost 1000 words and I’ve barely gotten past the first couplet. The whole point of these essays is to keep them short and digestible, and here I am straining at the form already. So let me wrap this up by formulating the questions I believe “In the Persian” is asking and which I believe are very relevant inside and outside of Kurd’s work:

What are we to do, inheritors of traditions we don’t fully understand that often exclude or alienate us? How do we access their richness and virtuosity while still maintaining a healthy contemporary skepticism about their origins in other languages, other times, other value systems?

Here’s what Rahat Kurd’s poem seems suggests as reponses:

- Study the tradition. If you need to, name drop the originators of 14th century (like Lal Ded) to the innovators of the 20th (like Faiz). Use your form with virtuosity and wit.

- Acknowledge the distance. Make your refrain “in the Persian” so that every time it repeats, we are reminded that the poem, the situation, and anything that can come from your efforts are seen through the gauze of an imperfect understanding.

- Then do it anyway. Despite, because of, and alongside these qualifications, doubts, and misunderstandings, make the poem into a baroque allusive delight using all of the nuances of the form at your disposal. Do your damned best to create an “improvised device” that is so powerful it can pull “Sunni closer to Shia.”

- Derive pride and nourishment both from your efforts to honour your inheritance, your acknowledgement of your imperfect gumption, and finally from your willingness to bend that tradition in order to conform its tropes to your own outlook and experience.

Does that seem like a lot to ask of an 18-line poem? Yes it does, which is why this one strikes me as so accomplished, even if I don’t have access to all the information it contains. I ride through it feeling like I must put up signposts to return to later, but also with a growing sense that I know the feelings she is referring to, in a different context and register – that is to say, in translation.

Beautiful. And what a great examination of the poem. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person